아이슬란드 출신 아티스트 비요크(Björk)가 그녀의 새로운 LP 앨범 [포소라(Fossora)]를 선보이며 음반의 콘셉트를 이야기하고, 고국 아이슬란드에서 시작된 경력 초기를 되새긴다. 그녀는 또한 자신이 가장 우려하는 글로벌 위기 상황을 지적하고, 현실에 대한 풍부한 지식과 함께 아이슬란드가 세계의 롤 모델이 되기까지 걸어온 길을 사색해 본다.

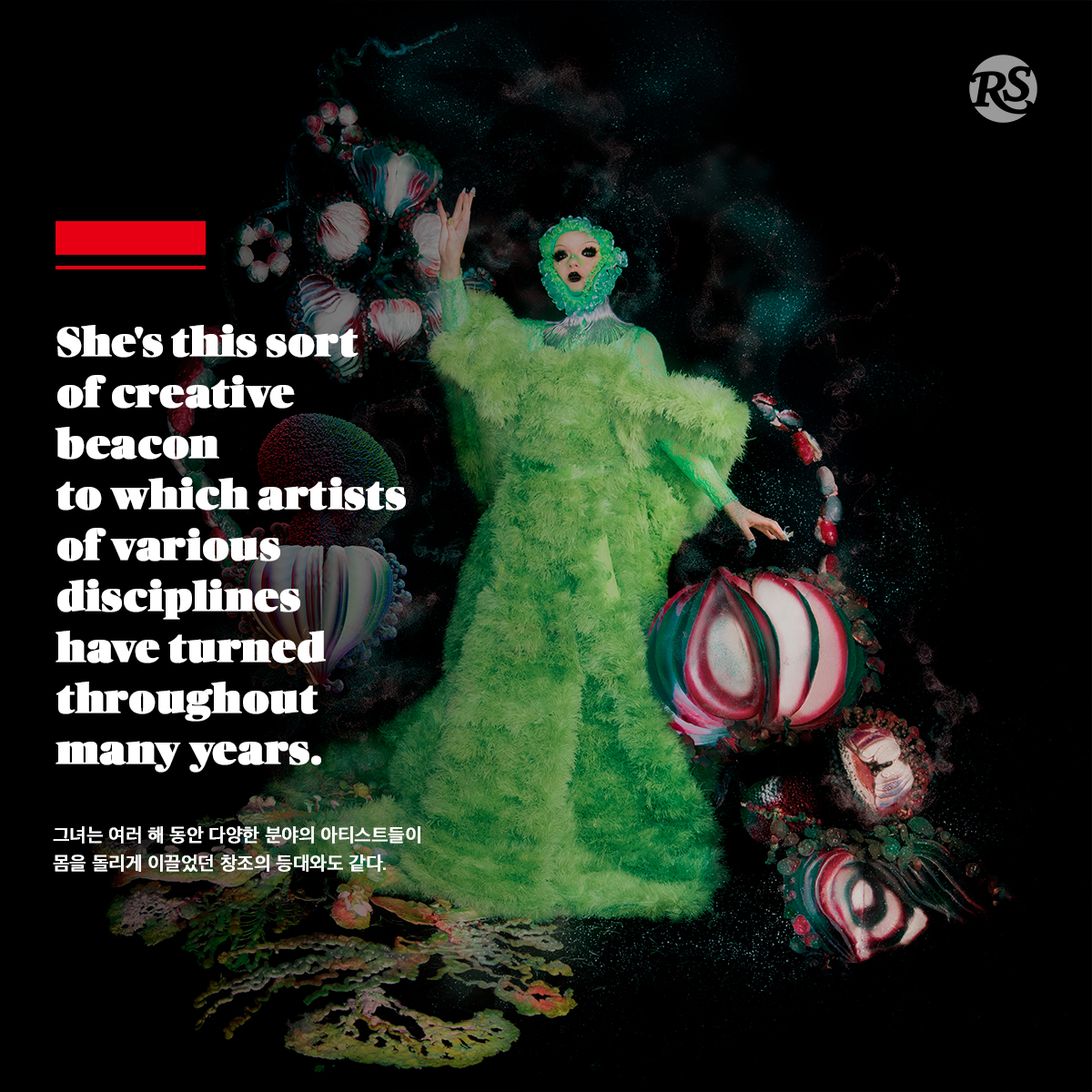

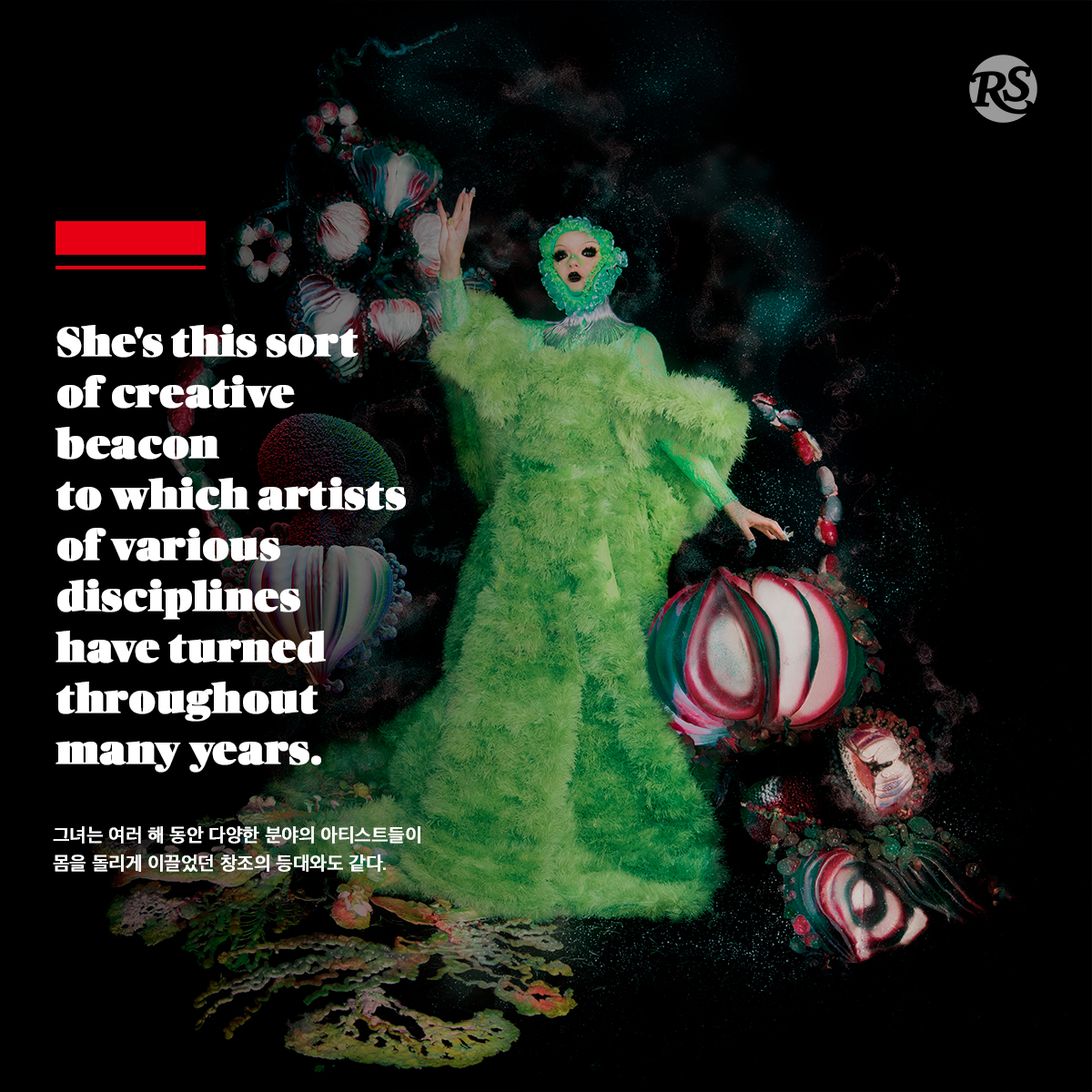

비요크(Björk)에게 묻고 싶은 질문이 너무나 많다. 그녀는 여러 해 동안 다양한 분야의 아티스트들이 몸을 돌리게 이끌었던 창조의 등대와도 같다. 누군가는 그녀의 목소리에 깃든 신비한 사운드, 그리고 그녀가 작품을 구성하는 모든 음향을 탐구할 때 그녀의 머릿속에서 일어나는 과정을 본인의 언어로 묘사해 달라는 청을 하고 싶을 것이다. 레이캬비크(Reykjavík) 거리의 펑크록 애호가에서 세계적인 음향 및 시각 전위 아티스트로 발전한 과정에 대한 그녀의 이야기를 듣는 것도 흥미진진할 것이다. 그토록 혁신적이고 도전적인 음악으로 주류 문화에서 성공을 거둘 수 있었던 이유를 직접 들어보는 것도 좋겠다. <Human Behavior>, <Army of Me>, <Bachelorette>과 같은 그녀의 근사한 뮤직비디오에 대해 궁금한 사람도 있을 것이다. 이들 뮤직비디오는 거장 미셸 공드리(Michel Gondry)가 창조한 걸작이다.

<어둠 속의 댄서(Dancer in the Dark)>를 통해 전해지는 그녀의 이야기와 가슴 아픈 열연에 대해 알아보는 것도 가치가 있을 것이다. 이 작품을 감독했던 라스 폰 트리에(Lars von Trier)는 제작 과정에서 성추행을 저질렀다는 혐의를 받고 있다. 전 세계의 많은 박물관에 비요크(Björk) 본인의 작품이 전시되어 있다는 이야기를 들으면서 우리는 그녀로부터 배울 것도 많을 것이다.

부모로부터 물려받은 사회의식이나 환경의식, 또는 그녀가 지지하는 다양한 분리주의 운동에 대해서도 몇 시간이고 이야기를 나눠볼 수 있을 것이다. 우리는 비요크(Björk)와 이러한 모든 주제 뿐만 아니라 다른 수천 가지에 대해 이야기해볼 수 있다. 그저 시간이 충분하지 않을 뿐이다. 특히 지금과 같은 새 앨범 발표 시기에는 더욱 그러하다.

연예인이라 부르기도 어려울 정도로 미리 꾸며낸 조악한 인격들과는 달리, 우리는 비요크(Björk)와 더없이 초월적인 주제들에 대한 대화를 나눌 수 있다. 그녀는 유구한 역사로 무장한 아티스트이다. 독특한 유산을 통해 온갖 통렬함과 뉘앙스가 가득한 중요성을 성취했고, 이는 그녀의 풍성하고 다양하며 심오한 작품에 반영이 된다.

우리는 8월 말에 그녀와 오랜 시간 이야기를 나눌 수 있는 기회가 있었다. 그 대화 내용을 정리하여 여기에 소개하고자 한다.

비요크Bjork, 새 앨범 [Fossora]에서는 당신의 음악적 뿌리, 그리고 가족의 뿌리를 엿볼 수 있다고들 해요. 거기에 대해 어떤 이야기를 해주실 수 있을까요?

글쎄요, 저는 코로나19로 인해 아이슬란드에서 지내는 것이 정말 즐거웠어요. 정말 근사했었죠. 3년 동안 이곳에서 지내는 게 너무나 좋았어요. 걸어서 동네 카페며 수영장에 다니고, 친구들과 가족들을 모두 만나고, 지역 음악가들과 함께 작업도 했어요. 저에게는 즐거운 시간이었어요.

아이슬란드에서는 팬데믹이 그렇게 견디기 힘들지는 않았나 봐요.

맞아요, 여기 아이슬란드에서는 규제가 그리 엄격하지 않았죠.

머시룸(버섯)이라는 콘셉트를 통해 [Fossora]에서 전달하려는 것은 무엇인가요?

그건 제가 사람들에게 사운드의 세계를 설명하는 한 가지 방법이에요. 시각적인 지름길을 활용하면 사람들이 사운드의 세계를 더 잘 이해할 수도 있거든요. 제 생각에, 대부분의 사람들이 언어를 사용해서 사운드를 설명하는 것을 어려워하는 것 같아요.

마지막 전작이었던 [Utopia] 앨범에서는 구름 위에 뜬 섬 같은 사운드를 수집해 놓았죠. 마치 공상과학 소설 같았어요. 이런 얘기를 하는 이유는 모든 곡에 플루트 소리가 많이 들어갔기 때문이에요. 모두 공중에 뜬 느낌이었죠. 베이스도 비트도 거의 없이 모두가 공중에 둥둥 떠다녔어요. 제가 [Utopia]에서 <구름 속의 도시(city in the clouds)>라고 말한 것은 일종의 그런 의미였어요. 앨범의 사운드를 설명하는 시각적 지름길이었던 셈이죠. 새 앨범인 [Fossora]의 사운드는 지상에 좀 더 단단히 뿌리를 내리고 있어요. 베이스 클라리넷 6개를 사용했고, 지상에서 일어나는 많은 일들을 담아 냈죠. 그래서 제가 <Mushroom album>이라고 말하는 건 이런 균사체 같은 느낌의 사운드를 의미해요. 여기에는 다른 이유도 있어요. 이 앨범을 위해 녹음 작업이 5년 정도 걸렸는데, 그 때문에 모든 수록곡의 설명을 머시룸이라는 말로 퉁친다는 인상을 줄 수도 있어요. 사실은 서로 굉장히 다른 곡들인데도요. 하지만 제가 쓰는 머시룸이라는 말은 [Utopia]에서 구름 속을 떠다니는 것 같던 시기 이후에 땅에 내려와 착륙하는 것과 비슷하다는 뜻이기도 해요. 웃음 이곳 아이슬란드에서는 착륙 그 이상이죠. 한 곳에서 이렇게 오랜 시간을 보내다 보면 뿌리를 내릴 시간이 생기고, 탄탄하며 깊이 자리 잡게 돼요.

그러니 정서적인 측면에서 볼 때 제가 이 앨범을 머시룸 앨범이라고 부르는 것은 제가 탄탄히 뿌리를 내린 상태여야 하고 고요해야 한다는 뜻이에요. 우리 같은 뮤지션들은 때로 여행을 많이 해야 하는데, 그게 너무 버거울 때도 생기는 것 같아요.

당연한 말이지만 [Fossora]에는 유기적인 사운드가 많이 들어 있어요. 머시룸 콘셉트와 연결되는 의미는 분명하죠. 지금껏 만들었던 다른 앨범만큼 일렉트로닉하다는 느낌이 별로 없어요.

밸런스는 사실 비슷한 것 같아요. 지난 앨범과 마찬가지로 이번에도 플루트를 넣었거든요. 그리고 이전 앨범에는 현악기가 있었어요. 이처럼 저는 항상 어쿠스틱 악기를 사용해 왔어요. 하지만 비트는 더 일렉트로닉하거나 디지털하다는 느낌을 줄 때가 많아요. 또는 제가 앨범을 직접 편집하기 때문에 보컬을 처리하는 역할이 될 수도 있고요. 저는 노트북으로 모든 것을 함께 편집하고, 비트를 추가하는 작업에 오랜 시간을 보내요.

보통은 프로툴즈(Pro Tools) 소프트웨어나, 어쿠스틱 악기를 편곡할 수 있는 소프트웨어인 시벨리우스(Sibelius)로 작업을 하곤 해요. 이번 앨범의 디지털적인 면은 저의 다른 앨범들과 비슷한 느낌인 것 같아요. 아날로그와 디지털이 이루는 밸런스가 좋아요. 저는 이 둘이 친구가 되고, 둘이 함께 잘 어울리는 게 좋아요. 제 이상형 세계에는 이 두 가지가 모두 다 있어요. 우리에겐 친구가 있고, 연인이 있고, 가족이 있어요. 이들은 살과 피로 된 실제 사람들이고요. 하지만 우리에게는 휴대폰도 있죠. 아시다시피 인터넷이며 이런 저런 게 있잖아요. 그런 건 상당히 현실적이고, 실제로 우리가 살아가고 있는 삶과 비슷해요.

<Atopos>나 <(Ovule>같은 곡 등에 나타난 [Fossora]의 어떤 부분은 뭐랄까, 라틴 음악의 영향을 받은 것 같아요. 그와 관련해 해주실 이야기가 있나요? 제가 잘못 짐작한 걸까요?

웃음 아니에요, 레게톤 비트를 말씀하시는 것 같네요.

아마 그 얘기일 거예요. 약간의 뎀보(레게톤 비트)가 있거든요.

이유는 모르겠지만, 그 곡들에서는 레게톤 비트를 썼어요. “레게톤 비트를 좀 써봐야지” 이렇게 생각하고 한 건 아니었어요. 의식적인 건 아니었지만, 모든 것을 하나로 묶을 수 있는 형태가 그거였어요. <Atopos>는 클라리넷과 트롬본의 편곡이고, <Ovule>의 모든 작업은 꽤 복잡했거든요. 그래서 모든 것을 하나로 묶어줄 수 있게끔 큰 에너지를 발휘하면서도 정말 간단한 비트가 필요했죠. 그리고 레게톤 비트는 이런 식으로 만들었어요. 웃음 처음에는 아주 기본적인 사운드로 비트를 직접 시도해봤어요. 그런 다음 나중에 사운드를 변경했지만, 사용한 비트 구조는 동일했죠.

잘 모르겠네요. 란사로테(Lanzarote) 섬에 있을 때 이 곡들 작업도 하고 있었거든요. 앨범 작업 초반에 두 번 다녀왔어요. 거기에서 현지 라디오를 들으며 지내다 보니 저도 모르게 영향을 받았는지도 모르죠. 그리고 이번 앨범 작업 초반에는 바르셀로나에서 아르카(Arca), 로살리아(Rosalia), 엘 긴초(El Guincho)와 자주 어울리기도 했어요. 거기에서도 영향을 받았을지 모르겠네요. 잘은 모르겠지만, 의도적으로 넣은 것은 아니었어요 당시에 듣던 비트가 있었다면 대부분은 우간다 테크노 같은 동아프리카 음악이나 아프로비트였을 거예요.

레게톤과 공통점이 많죠.

맞아요. 비트 구조가 비슷해요.

카리브 해의 댄스홀에서도 똑같은 일이 일어나곤 해요. 그 기원이라고 할 수 있겠네요…

맞아요, 아마 그 영향을 많이 받은 것 같아요. 일종의 믹스였죠.

[Fossora]에는 당신의 어머니인 힐두르 루나 힉스도티르(Hildur Rúna Hauksdóttir)를 위해 작곡한 곡이 두 곡 들어 있지요. 그 이야기도 조금 해주실 수 있을까요?

제 어머니는 4년 전에 돌아가셨어요. 어머니가 돌아가시기 1년 전에 곡을 하나 썼고, 그 직후에 또 다른 한 곡을 썼어요. 어머니를 기리는 일종의 추도문과 비문 같은 거예요. 저는 장례식에 대한 생각이 굉장히 구체적인 것 같아요. 항상 장례식에 참석하는 것이 무척 어려웠어요. 장례식은 내부에서 비공개로 치러지니까요. 저는 장례식이 외부에 드러나 있기를 바라요. 어떻게든 돌아와 자연과 다시 하나가 되잖아요.

그래서 어머니가 떠나신 후 쓴 곡 <Ancestress>는 제가 어머니를 위해 어떤 의식을 치러드리는 기분이었어요. 장례식과 같지만, 내부가 아닌 외부에서 치르는 거죠. 뮤직비디오는 지난 6월에 찍었는데, 이를 공유할 수 있어 무척 기뻐요. 대략 한 달 내에 나올 거예요. 남자 형제에게 작업에 함께 참여해 달라고 부탁했어요. 일종의 야외 장례식 같았죠.

본인이 엄마가 된 상태에서 그런 곡을 쓰실 때 기분이 어땠어요?

와, 좋은 질문이네요. 그런 생각은 못 해봤어요. 그런 생각은 별로 없이 음악을 통해 반응하고 있었어요. 뮤지션들에게는 굉장히 충동적으로 행동할 기회가 많이 있죠.

제가 쓴 곡 중 많은 수가 자연스럽고 충동적인 반응에 가까웠던 것 같아요. 그 곡들 속에서는 만사가 어머니와 저, 둘 사이의 일이었죠. 그렇기에 제가 엄마가 된 것이 영향을 미쳤다는 느낌은 안 들어요. 하지만 가사 중에는 그런 말을 하는 순간이 있죠. 특히 <Sorrowful Soil>에서요. 아시다시피 여자 아이들이 태어날 때는 몸 안에 400개의 난자를 품고 태어나잖아요. 저는 항상 그게 참 아름답다고 생각했어요. 그리고 어떻게든 어머니의 이야기를 노래로 기록하고 싶었죠.

일반적으로 잡지나 신문에 부고를 알리는 기사는 사실만 딱딱 나열하잖아요. “태어났고, 이런 일을 했고, 이런 학교에 다녔고, 이 사람과 결혼했다”라는 식이죠. 그래서 부고라는 아이디어를 가져와서 좀 더 혈연답고 감성적인 느낌으로 만들고 싶었던 것 같아요. <Sorrowful Soil>은 어머니가 하셨던 작업의 이력에 관한 것이 아니에요. 그런 부고를 알리기는 것은 뭐랄까, 좀 남성적이고 가부장적인 방식이잖아요. 저는 그보다 좀 더 모계적인 부고 알림을 하고 싶었어요 “그녀는 400개의 난자를 품고 태어났으며, 그 중 2개는 인간으로 태어났습니다. 그리고 그녀는 삶을 잘 살았습니다.”

그리고 다른 곡인 <Ancestress>는 어머니의 삶에 대한 이야기에 좀 더 가까워요. 첫 소절은 제 어린 시절에 관한 것이고, 그 후부터 노래가 끝날 때까지는 연대 순으로 진행되는 내용이에요. 저는 어머니에 대해 일종의 혈연답고 감성적인 부고를 써보고 싶었다는 걸 알고 있었어요. 차가운 사실 위주의 알림보다는요. 어머니의 외적인 삶보다 내면의 삶을 더 많이 다루고 싶었죠.

앨범 작업에 아들 신드리(Sindri)와 딸 이사도라(Ísadóra)를 포함시키기로 결정하신 이유는 무엇인가요?

일종의 반응이었다고 생각해요. 아마 여러 가지 이유가 있었을 거예요. 확실한 이유 중 하나는 코로나19였어요. 여기에서 3년을 함께 지내다 보니 아이들과 많은 시간을 보냈거든요. 게다가 둘 다 성인이 되어서 그런지, 같이 작업하기 딱 좋은 때라는 느낌이 들었어요. 어머니에게 작별인사를 했을 때 제 아이들이 성인이 되었는데, 그럼으로써 이 때는 우리 가족에게 하나의 새로운 시기가 되었어요. 아이들 둘 다 많은 일을 하고 노래도 해요. 그래서 함께하는 작업이 무척 자연스럽게 느껴졌어요.

거의 11살 때 첫 앨범을 내셨죠. 그 때는 어떤 추억이 있나요?

전반적으로 이 앨범을 두고 저보다는 어머니가 더 신이 나셨고, 저는 수줍음이 많았던 것 같아요. 아이슬란드에서 아주 좋은 성적을 거두었기에 어머니는 앨범을 하나 더 만들자고 하셨지만, 저는 그러고 싶지 않았어요. 그런 다음 펑크 밴드를 시작했고 15년 정도 이런저런 밴드를 계속했어요. 너무 이른 시기에 주목 받는 자리로 떠밀려 나왔던 것 같아요. 저는 그게 좋지 않았어요. 그룹으로 일하는 게 좋았고, 그룹 작업을 진심으로 즐겼죠.

16년 쯤 지나서 두 번째 앨범이 나왔을 때 앨범 이름을 [Debut]라고 지었어요. 웃음 그 때 비로소 앨범을 마주할 준비가 된 것 같았어요. 제가 모든 곡을 썼고, 그게 제 작품이었고, 제 삶이었고, 따라서 전보다 더 진실하다는 느낌이 들었으니까요. 11살에 첫 앨범이 나왔을 때는 제가 거짓말쟁이가 된 것 같은 기분이었어요. 다른 사람들이 모든 작업을 다 해주고, 저는 그저 얼굴이나 표지 역할만 하는 것 같았거든요.

하지만 스튜디오 경험은 정말이지 즐거웠어요. 사랑에 마지않았고 진심으로 감사했어요. 히피 (Hippie)세대의 멋진 사람들이 저와 함께 작업해 주었고, 마이크 앞에서 노래하는 법이며 단어를 발음하는 법을 가르쳐 주고, 굉장히 친절하게 대해 주셨어요. 맞아요, 히피족 속에서 자라고 스튜디오 경험을 할 수 있었던 게 아주 큰 축복이었다고 느껴요. 그 분들은 매우 훌륭한 선생님이었고 아이들과도 아주 잘 지냈어요. 그리고 제가 아이로 지낼 수 있는 여지를 많이 허락해 주셨어요. 그리 흔한 일은 아니었죠. 그러니 이런 면에서 저에게 긍정적인 경험이었다고 생각해요.

스튜디오에서 작업하는 건 정말 좋았어요. 11살의 나이에 길거리에서 다른 사람들이 절 알아볼 정도로 대중적인 존재가 되는 건 하나도 좋지 않았고요. 그건 끔찍하게 싫었어요.

아까 밴드 이야기를 하셨죠. 슈가큐브스(The Sugarcubes)는 많은 사람들에게 무척 좋은 기억으로 남아 있는 밴드예요.

네, 처음에는 쿠클(Kukl)이라는 밴드에서 활동했고 그 다음에는 The Sugarcubes에서 10년 동안 활동했어요. 두 밴드 모두 똑같은 멤버가 셋 있었죠. 다른 가수 에이나르(Einar), 외른 베네딕츠손(Örn Benediktsson), 드러머 식트리귀르 발뒤르손(Siggtryggur Baldursson), 그리고 저 자신 이었어요. 제 삶에서 아주 놀랍고 멋진 시기였고, 우리는 서로의 스승이 되어주었던 것 같아요. 정말이지 재미있었어요. 펑크 에너지가 원천이 되던 가운데 우리는 곡도 발표해야 했죠. 우리 작업물의 저작권도 소유하고, 포스터와 앨범 표지도 만들었어요. 모든 걸 우리 스스로 다 해냈어요. 제 삶에서 정말로 중요한 시기였어요.

활동을 시작하신 이래, 여성을 대하는 방식과 관련해 음반업계에는 어떤 발전이 있었나요?

아이슬란드에서는 큰 차이가 없어요. 우리는 여성 권리 관련한 부문 대부분에서 언제나 전 세계 상위 3위에 들거든요. 저는 히피 가정에서 자랐어요. 그리고 아이슬란드는 이런 면에서 굉장히 자유주의적인 나라죠. 그래서 저는 정말로 큰 차이를 느끼지 못했어요.

제 생각에는, 다른 나라로 여행을 하기 시작했을 때 그런 차이를 더 많이 알아차리게 된 것 같아요. 특히 영화계와 같은 다른 분야에서는 정말로 큰 차이가 있어요. 엄청난 변화가 있었고 지금도 그런 변화가 일어나고 있다고 생각해요.

비요크(Björk), 아이슬란드는 어떻게 그토록 많은 분야에서 세계의 롤 모델이 될 수 있었을까요? 예를 들어 교육이 그렇죠.

우리는 여기에서 문제가 많다는 점을 분명히 해 두고 싶어요. 아이슬란드는 이 부분에서 천국이 아니에요. 이 인터뷰에서 이곳이 지상천국인 양 보이게 하고 싶지는 않아요. 우리가 해결해야 할 문제들은 확실히 많이 있거든요. 하지만 세계화와 환경 문제가 만연한 이 시대에 우리가 많은 일을 잘 해내는 이유 중 하나는 우리가 작은 섬에 살고 있기 때문이라고 생각해요. 사실 인구가 360,000명인 것에 비하면 굉장히 큰 섬이에요. 웃음 우리 섬의 크기는 영국만 하죠.

여기에는 자연과 공간이 아주 많아요. 제 생각에 우리는 자연과 기술이 서로 어우러져 건강한 균형을 이루고 있어요. 저는 유럽의 한 수도에 살고 있지만, 동시에 산으로 둘러싸인 해변이라는 자연 속에서 살고 있죠. 많은 도시가 환경 문제에 직면해 있는 지금 같은 때에 아이슬란드의 이러한 자연과 문명 사이의 균형은 건강하기도 하고 관리하기도 쉬워요.

그리고 우리가 600년 동안 덴마크의 식민지로 살면서 아주 나쁜 대우를 받은 것도 한 가지 이유라고 생각해요. 제 생각에, 사람들이 독립을 한 후에는 항상 이런 현상이 일어나는 것 같아요. 첫 번째 세대가 태어나고, 두 번째 세대가 태어나고, 그러고 나면 독립을 축하하는 것과 같죠. 우리가 이런 질문을 50년 전에 받았다면, 지금처럼 좋은 위치에 있지는 못했겠죠. 하지만 지금 우리는 유리한 위치에 있어요. 적정 시간 동안 자신을 인정해 왔으니까요. 우리가 50년 동안 어떻게 지냈는지 한번 살펴보죠. 어쩌면 죄다 망쳐버렸는지도 몰라요!

이곳 아이슬란드에서는 여성들이 꽤 강하다는 것 역시 아마 사실일 거예요. 제 생각에는 아이슬란드가 유럽에서 멀리 떨어져 있는 덕분에 일종의 모계 국가가 될 수 있었던 것 같아요. 이 주제로 몇 시간은 이야기를 나눠야 할 거예요. 웃음 이건 복잡한 문제인데, 아마 이것으로 말미암아 21세기로 진입하는 기회가 굉장히 신속하게 이루어졌다고 생각해요. 일부 다른 문화에 비해 빠른 속도였을 거에요.

그리고 우리가 600년 동안 식민지로 있었기 때문에 다른 스칸디나비아 국가들로부터 혜택을 받았다고도 생각해요. 식민지 경험은 끔찍했지만, 한편으로 사회주의, 병원, 교육 같은 것과 관련해서는 가장 좋은 부분만 골라서 취한 거죠.

일부 국가가 자본주의든 사회주의든 상관없이, 대부분의 국가는 자본주의 국가라고 생각해요. 그리고 교육체제와 의료체제는 사회주의 체제에서 더 낫다는 데 동의해요. 사회주의 체제에서는 이런 것들이 무상으로 공급되니까요.

네, 아이슬란드에는 좋은 점이 많이 있어요. 하지만 우리에게도 문제가 많다는 점을 말씀드리고 싶어요. 아이슬란드를 하나의 거대한 알루미늄 공장으로 만들고 싶어 하는 “산업주의자(industrialist)”들이 많이 있어요. 이 사람들을 뭐라고 불러야 할지 모르겠네요. 우리는 날마다 이들을 상대로 싸워야 하죠. 아시겠지만 흑과 백이 명명백백한 문제가 아니에요.

아이슬란드를 생각하면 칼레오(Kaleo), 오브 몬스터스 앤 맨(Of Monsters and Men), 시규어 로스(Sigur Rós)가 떠올라요. 아이슬란드는 작은 나라이지만서도 세계에 좋은 음악을 많이 전하고 있어요.

네, “이렇게 된 이유가 뭘까?”라는 질문을 많이 받아요. 확실히 저는 잘 모르겠네요. 웃음 하지만 아이슬란드 음악의 좋은 점 중 하나는 레이캬비크(Reykjavík) 의 크기가 아닐까 생각해요. 마치 하나의 마을 같아서 시내 어디든 걸어서 갈 수 있고 자동차가 필요하지 않죠. 콘서트에 갔다가 5분 정도 걸으면 미술품이 설치되어 있고, 거기서 또 5분 정도 걸으면 연극 공연을 만나게 돼요. 모든 것이 셀프로 이루어지고 예산이 매우 낮아요. 이런 일을 세계적인 명성을 얻으려고 하는 사람은 아무도 없어요. 아이슬란드에서는 음악만으로 돈을 벌 수 없어요. 음악을 사랑하기 때문에 해야만 하는 거죠.

14-15세에서 25세 사이의 아이들은 그저 본인이 사랑한다는 이유만으로 음악을 하고 있고, 이 아이들이 만드는 음악을 들어주는 사람들이 있어요. 저는 그게 교육적으로 좋은 정책이라고 생각해요. 그 시기가 지나면 다른 나라로 갈 준비가 되는 거죠. 뮤지션들에게는 좋은 온상과도 같은 곳이에요.

예를 들어, 제 생각에 아이슬란드에서는 영화를 만드는 것이 더 어려워요. 인구가 360,000명에 불과한 나라이다 보니 영화를 만들기에는 규모가 너무 작죠. 어려운 일이에요. 여기에는 예산도 없고요. 밴드 활동은 큰 돈을 들이지 않고 수월하게 할 수 있어요. 가끔 런던이나 뉴욕 같은 대도시에 갈 때, 밴드 활동을 하기가 더 어렵다는 걸 알 수 있어요. 도시 규모가 워낙 거대하다 보니 무척 복잡하기도 하고, 음악을 들려주고 알려지기까지의 경쟁도 너무나 치열하죠. 여기에서는 뭔가를 발표하고 콘서트를 한 번 하면 모든 사람이 얼굴을 알아볼 정도예요. 그러니 아이슬란드는 십대 청소년이 밴드 활동을 하기에 좋은 곳이에요. 아주 좋은 곳이죠. 무슨 뜻인지 아시죠?

영화 이야기를 좀 해보죠. 최근에 영화 <노스맨(The Northman)>에서 연기를 하셨는데요. 맡은 배역인 예언자(the Seeress)에 대해 이야기 좀 들려주세요.

제 친구인 숀(Sjón), 시귀르욘 비르기르 시귀르드손(Sigurjón Birgir Sigurðsson)에게 보내는 일종의 호의였다고 생각해요. 숀은 로버트 에거스(Robert Eggers)와 함께 이 작품의 각본을 맡았죠. 제가 두 사람을 소개시켜 줬는데 숀이 저더러 참여를 요청했어요. 저는 숀과 친구 사이예요. 숀은 아이슬란드 작가인데, 아시는지 모르겠지만 <Bachelorette>과 <Isobel>, 그 밖에 여러 곡의 가사를 썼어요.

우리는 16살 때부터 친구로 지냈기 때문에 한쪽이 다른 한쪽에게 뭘 해달라고 하면 그냥 ‘그래’라고 대답하는 사이에요. 웃음 숀은 제게 ‘그래’라고 대답해 준 적이 아주 많았기에 이번에는 제가 ‘그래’라고 말해 주고 싶었어요. 그리고 저는 아이슬란드의 유산을 계승하고 바이킹족 세계를 다른 관점에서 보여주기 위해 무게를 실어주는 데도 관심이 있었거든요.

제 생각에 바이킹족 문화는 굉장히 오해를 많이 사는 것 같아요. 아이슬란드로 온 바이킹족의 경우는 특히 더 그렇고요. 영국인들과 바이킹족은 서로 적대관계였어요. 역사서를 쓴 것은 영국인인데, 이들이 파괴할 수 없었던 유일한 상대가 바이킹족이었기에 그들이 바이킹족을 이런 괴물 같은 존재로 만들어버린 거죠.

솔직히 말해서 바이킹족은 당시의 다른 문화들과 별반 다르지 않았다고 생각해요. 영국인이 하는 소리치고는 너무 세다며 친구들과 웃을 때도 있어요. 영국이 식민지로 만든 나라들이 얼마나 많아요? 전 세계 70개국 정도는 되지 않나요? 웃음 그리고 오늘날에는 고고학 분야의 첨단기술 발전 덕분에 DNA를 통해 더 많은 것을 발견하고 있는게 너무 흥미로워요. 이를 통해 바이킹족이 융성한 문화와 시와 수많은 신화를 자랑했고, 매우 복잡한 존재였으며, 수많은 공예품을 보유했다는 사실도 이제는 알게 되었고요. 이들은 그저 단순한 살인기계가 아니었어요. 물론 이들도 폭력적이기는 했지만, 서기 1000년경에는 어느 문화든 군대는 다 있었을 거예요.

언제나 행동주의를 무척 중요하게 여기셨죠. 환경 운동을 지원하고, 여러 운동 중에서도 티베트(Tibet), 코소보(Kosovo), 미투(Me Too) 운동을 위해 활동하셨는데요. 지금 우려되는 문제는 무엇인가요?

제게는 언제나 환경 문제가 가장 중요해요. 특히 다음 세대를 위해서 지금 행동에 나서야 한다고 생각해요. 우리가 할 수 있는 모든 일을 절대적으로 모두 하지 않는 한, 지금 태어나고 있는 세대에게 양심의 가책 없이 지구 행성을 물려줄 수 없을 거예요.

그리고 저는 사람들이 코로나19 팬데믹 사태를 맞아 전 지구와 각국 정부가 얼마나 신속하게 공동 행동을 취하면서 모든 국가를 폐쇄하고 백신을 개발할 수 있는지 알게 되길 바랐어요. 그런 조치는 참으로 신속하게 이루어졌죠. 이전에는 그렇게 발 빠른 조치를 취한 적이 단 한 번도 없었어요. 저는 사람들이 환경 문제로 눈을 돌려 비상 사태를 맞은 것처럼 행동해 주기를 바랐어요. 실제로 비상 사태가 맞기도 하고요. 이런 일이 제 기대만큼 빠르게 일어나 주지는 않았죠. 저를 포함해 우리 모두가 더 많은 일을 해야 한다고 생각해요.

팬데믹은 자연이 인류에게 보내는 메시지라고 생각하세요?

그럼요. 우리는 팬데믹에서 벗어날 수 있지만, 귀 기울여 그 메시지를 들어야만 해요. 저는 이것이 세대적인 문제라는 사실에 희망을 걸어왔어요. 지금까지 전 세계에서 집권해 온 사람들과 정치인들이 이제는 70대 정도 되었지 싶어요. 우리 세대가 최고령 세대가 되고 새로운 세대가 들어올 때쯤이면 지금 현재 지구에 악영향을 미치는 결정을 내리고 있는 권력자들을 몰아낼 수 있게 되길 바라요. 하지만 그럴 만한 시간이 있을지는 모르겠네요. 상황이 썩 좋아 보이지는 않으니까요.

Photographs by Viðar Logi

Björk: Beyond the Mushroom Sound

The Icelandic artist presents her new LP, “Fossora”, talks about the concept around the record, and reviews her early career, all from her homeland. She also points out the global situation that concerns her most and reflects -with full knowledge of the facts- on the path Iceland has taken to become a role model for the world

By RICARDO DURÁN

There are too many things one would like to ask Björk. She's this sort of creative beacon to which artists of various disciplines have turned throughout many years. One would like to ask her to describe in her own words the mysterious sound of her voice and the processes that take place in her head as she explores all the sonorities that make up her work. It would be fascinating to hear her talk about the evolution that led her from punk in the streets of Reykjavík, to the sound and visual avant-garde of the world. Hear her explain her success in the mainstream by making such innovative and challenging music. Ask her about the wonderful music videos for 'Human Behavior,' 'Army of Me,' or 'Bachelorette' - true masterpieces created with the grand Michel Gondry.

It would also be worthwhile to find out her story and her heart-wrenching performance in Dancer in the Dark, being directed by Lars von Trier, who ended up accused of sexual harassment during production. We'd learn a lot from hearing her talk about her work's presence in many museums worldwide.

One could talk to her for hours about the social and environmental awareness she inherited from her parents or her support for different separatist movements. One could talk to her about all this and a thousand other things - there just isn't enough time, especially now, when she's presenting a new album.

However, any conversation with Björk can end up tackling the most transcendental issues, unlike many prefabricated personalities that can hardly receive the title of entertainers. She's an artist with history, with a unique legacy that leads her to reach an importance full of edges and nuances, reflections of a rich, diverse and profound work.

We had the opportunity to talk to her for a long time at the end of August. This is the result of our discussion:

Bjork, it has been said that your new album, “Fossora”, represents a glimpse into your musical and family roots. What can you tell us about it?

Well, I did really enjoy being in Iceland here for Covid, it was amazing. I really loved to be here for three years, walk to my local cafe and swimming pool and meet all my friends and family, and work with the local musicians. This has been enjoyable for me.

In Iceland, the pandemic wasn't that hard for people to go through.

No, the restrictions were not so much here in Iceland.

What do you want to communicate in “Fossora”with the mushrooms concept?

It's a way for me to explain to people the sound world. Sometimes, when you use visual shortcuts, people understand better sound worlds. I feel most people find it hard to use words to describe a sound.

On my last album, “Utopia”, I collected like an island in the clouds; it was like a sci-fi story. The reason why I say this is because in all the songs there were a lot of flutes. It was all in the air, there was almost no bass nor beat - it was all floating in the air. When I said "city in the clouds" in “Utopia”, that's sort of what I meant. It was a visual shortcut to describe the sound of the album. The sound of the album, my new one, “Fossora”, is more grounded; six bass clarinets and a lot of things happening on the ground. So, when I say "mushroom album", I mean this, that sort of fungus sound. But there are other reasons to... this album I recorded over a five-year period, but that is also why mushrooms would kind of describe all the songs because they're obviously very different from each other. But also, when I say mushroom, I mean it's sort of like my landing after my “Utopia” cloud period. [Laughs] It's more of a landing here in Iceland. When you spend so long in one place, you have time to shoot down roots and you get very grounded.

So, emotionally, when I call it a mushroom album, it just means that I got to be very grounded and very, you know, calm. I think sometimes we musicians have to travel a lot, I think it can sometimes be too much.

Naturally, there are a lot of organic sounds in “Fossora”. The relation to the mushroom concept is obvious; it's not as electronic as other albums you've made.

I think the balance is actually similar, like the last album, I had flutes. And the album before, I had strings. So, I've always had acoustic instruments. But usually, the beats are more electronic or digital, or my treatment on my vocals because I edit my albums myself. I spend a lot of time on the laptop editing everything together and adding the beats.

I usually work with the Pro Tools software or Sibelius, which is a software where you can make arrangements for acoustic instruments. I think the digital side of this album feels similar to my other albums. The balance between analog and digital, I like both to be friends, I like them to get along, and in my ideal world, you have both. You have friends and you have lovers and you have your family, and they're real people with flesh and blood. But you also have your phone, and you know, the Internet or whatever. It's actually quite realistic or similar to the lives that we are living, you know.

Some parts of “Fossora” -songs like 'Atopos' or 'Ovule'- seem to have some kind of Latin influence, what could u tell us about that? Am I wrong?

[Laughs] No, I guess you're talking about the reggaeton beat.

Probably, yeah, there’s some dembow there…

I don’t know why, I wrote those reggaeton beats for those songs. I wasn't thinking, “Oh, let's do a reggaeton beat”. It was unconscious, but it was the shape that could pull everything together, because the arrangements of the clarinets in ‘Atopos’, and also the trombone, and everything in ‘Ovule’ is quite complex. So I needed like a really, really simple beat with a lot of energy that could pull everything together. And reggaeton beats are like this. [Laughs] I just did the beats myself first, with very basic sounds, and then, afterwards, we changed the sounds on them, but used the same beat structure.

I don’t know. I was also working on these songs when I was in Lanzarote. In the beginning of the album, I went there two times. I was listening to the local radio station there, so it might have influenced me without me knowing. Also, at the beginning of this album I was hanging out a lot in Barcelona with Arca and Rosalia and El Guincho. So this maybe also influenced me or something, I’m not sure, but it was not intentional. If I was listening to any beats, it was mostly likely East African like techno from Uganda and stuff like that; afrobeat.

It has a lot in common with reggaeton.

Exactly, the structure of the beat is similar.

The same thing happens with dancehall from the Caribbean, where it originates…

Exactly, I think it probably influenced me a lot. It was some sort of a mix.

“Fossora” contains two songs written for your mother, Hildur Rúna Hauksdóttir. Would you like to tell us a bit about that?

She passed away four years ago and I wrote one song about her like a year before she passed, and then one straight after. This is like a sort of eulogy and epitaph for her. I feel like I have very specific ideas about funerals, it has always been very difficult for me to go to funerals because they're inside. I would like them to be outside - you are getting back, reunited with nature, somehow.

So 'Ancestress', the song I wrote after she passed away, it's like if I could make a ritual for her, like a funeral, but outside. We filmed the video last June, I'm very excited to share that. It will come out in a month or so. I asked my brother to be part of it and yeah, it's sort of like an outdoor funeral.

How did you feel writing those songs being yourself a mother?

Wow, it's a good question, I hadn't thought of that. I wasn't thinking so much about it, I was more reacting through music. For a lot of musicians, you have a chance to be very impulsive.

I guess many of the songs that I wrote were more like a natural, impulsive reaction, in which everything was between her and me. So I didn't feel me being a mother influenced that. But there is a moment in the lyrics, especially in 'Sorrowful Soil,' where I'm talking about, you know, when girls are born, when they are born with 400 eggs inside. I always thought that was very beautiful. And, somehow, I wanted to document her story in the song.

Usually, when you read an obituary in the magazine or in the newspaper, it's very like factual - "they were born, they did this job, they went to this school, they married this person." So I think I wanted to take the idea of the obituary and make it more biological and emotional. 'Sorrowful Soil' is not about her work history, which is sort of masculine, sort of a patriarchal way to do an obituary, but I wanted to do more like a matriarchy obituary. "She was born with 400 eggs, and two of them became human beings, and she did well."

And then, 'Ancestress,' the other song, is more about her life story. The first verse is about my childhood, and then it's in chronological order all the way until the end of the song. I was conscious that I wanted to write some sort of biological and emotional obituary of her - not like a cold factual one. More about her inner life then her outer life.

Why did you decide to involve your son Sindri and your daughter Ísadóra on the album?

I think it was some sort of reaction, maybe there were several reasons. One of them was Covid, for sure. We were here together for three years, so I was seeing them a lot. Also maybe because they're both grown-ups, so it felt like the right moment. Saying goodbye to my mother was also like a new period in our family, in which my children are grown-ups, they both do many things, and they both sing as well, so this felt like a very natural thing to do.

You released your first album when you were barely 11 years old. What memories do you have of that time?

Overall, I feel my mother was more excited about this album than I was, and I was very shy. It did very well in Iceland, my mother wanted to make another one, but I didn't want to do it. Then I started in punk bands and was in bands for like 15 years after that. I think I was pushed into the lights too early. I didn't like it. I liked very much to work in groups, and I really enjoyed group work.

When my second album came out, which I named 'Debut,' [Laughs] like 16 years later, I think I felt like now I was ready to front an album because I wrote all the songs myself and it was my work, it was my life, it felt more truthful. The first album, when I was 11, I felt like I was lying because everybody else did all the work and I was just like a face or a front to it.

But I did very much enjoy the experience of being in the studio, that I really, really loved, and I'm really grateful. There were a lot of amazing people from the hippie generation working with me, teaching me how to sing in a microphone, teaching me how to pronounce words and there were very kind to me. And yeah, I feel very blessed I was brought up by hippies and also in the studio too. They were very good teachers, they were very good with kids. And they gave me a lot of room as a kid, which I don't think is very common, so I think this experience was positive for me in this way.

Working at the studio, yes, I loved; being recognized in the street and kind of becoming a public persona, at 11, I did not like that at all. I really hated that.

You were talking about your bands, and The Sugarcubes is a band many remember very fondly.

Yeah, I was first in a band called Kukl, and then in The Sugarcubes for 10 years. They both had the same three people: the other singer Einar [Örn Benediktsson], the drummer Siggtryggur [Baldursson], and me. So it was kind of a very amazing period in my life, and it was like we were each other’s teachers. It was really, really fun, we were also coming from the punk energy where we had to publish ourselves, we would own the rights to our own work and we would make posters and the album cover - everything ourselves. It was a really important period in my life.

How has the music industry evolved since you started, in regards to the way it treats women?

In Iceland there isn't much difference, we are always top three for most rights for women in the world. I was brought up by my hippie family and also Iceland, which is a very liberal country in this way. So I never really felt much difference for me.

I think [I noticed] it more when I started traveling to other countries, where I could see some differences, especially in like other disciplines, like the film world, for example, where it’s really, really different. I think there's been a huge change and I think it’s still happening, for sure.

Björk, how has Iceland managed to become a role model for the world in so many areas? Education, for example.

I think I want to make clear that we do have a lot of problems here - it’s not paradise. I don't want to come across in this interview like this is the best place on Earth, we have a lot of issues we need to work on, for sure. But I do think one of the reasons why we are doing well in many things, in this time of globalization and environmental problems, [is that] we are living on a small island. It’s actually a big island [Laughs] compared to how many people live here, 360,000 people, and our island is as big as England.

There's a lot of nature and a lot of space here, and I think the balance between nature and technology here is very heathy, the balance between urban and… I live in a European capital, but I live in nature, on a beach surrounded by mountains. The balance between nature and civilization is very healthy and more manageable, when many cities are finding themselves with the environmental problems.

I also think it’s because we were a Danish colony for 600 years, we got treated very badly. So I think this always happen after people become independent – the first generation is born, then second generation, then it’s like a celebration of their independence. I’d say, if you would have asked [this to] us 50 years ago, we would not have been in a good position. But, right now, we are in a good position because we have owned ourselves for just the right amount of time. Let's see how we are doing in 50 years, maybe we fucked it all up!

Maybe it’s also the fact that women are quite strong here. I think because we are so far away from Europe, Iceland sort of became a matriarchy. This is something we should talk about for many hours. [Laughs] It’s a complex matter and I think this made the scope very quickly into the 21st century, quicker than maybe some other cultures.

I think we have also benefited from the other Scandinavian countries, because we were a colony for 600 years and it sucked, but at the same time, when it comes to socialism and hospitals and education, things like this, we picked up the best parts.

Even though some countries are capitalist or socialist or whatever, I guess most countries are capitalist countries, agree that the education system, as well as the health system, are better in a socialistic system, where they’re free.

So yeah, there are a lot of good things about Iceland, but I mean, we do have a lot of problems too. We have a lot of, I don’t know what to call them, “industrialists” here that want to make Iceland into one big aluminum factory, and we have to fight it every day. It’s not so black and white, you know.

When you think about Iceland, you think about Kaleo, Of Monsters and Men, Sigur Rós; being such a small country, Iceland has been giving the world a lot of good music.

Yeah, I get asked this a lot, “Why is this like it is?” I obviously don’t know. [Laughs] But I do think that one thing that is good for music here in Iceland is the size of Reykjavík. It’s like a village, you can walk everywhere downtown, you don’t need a car. You go to one concert, you walk five minutes and then there's an art installation, and then you walk for five minutes and there's some theater piece. Everything is very DIY and very low budget, nobody is doing it to become world famous. In Iceland you cannot make money from making just music, you have to do it because you love it.

Kids from 14 or 15 until 25, they're doing it just because they love it, and you have all these other people listening to what they are doing and stuff. I think it’s a good educational curve, and then after that you're ready to go to other countries. So it’s almost like a good breeding ground for musicians,

I think it’s harder in Iceland, for example, if you're making films. We are so small to make a film in a country with other 360,000 people. It’s difficult, there's no budget here. Being in a band doesn't cost a lot of money, it’s very easy. Sometimes, when I’m in big cities like London or New York, I see that it is more complicated to be in a band, the city is so big it’s very complex and in order to be heard, there is so much competition. Here, you release something and do one concert, everybody knows who you are. So, it’s a good place to be a teenager in a band, very good place, if you know what I mean.

Let’s talk about movies. You recently acted in the movie “The Northman”, please tell us about your character, the Seeress.

I think it was sort of a favor to a friend, Sjón [Sigurjón Birgir Sigurðsson], who wrote the script with Robert Eggers. I introduced them and then Sjón asked me to be in it. My friendship with Sjón, he's an Icelandic author; I don’t know if you know, he wrote lyrics for song like 'Bachelorette' and 'Isobel' and other lyrics.

We've been friend since I was 16, so we have this kind of friendship if one person asks the other one to do something, you say yes [Laughs] and he has said many yes's to me, so I wanted to say yes to him. I was also interested in getting some heavy weight to take on the Iceland heritage and show Vikings in another light.

I think they are very misunderstood culture, especially the ones who came to Iceland. The English and the Vikings they were enemies. The English wrote the history books and the Vikings were the only ones they couldn't destroy, so they made the Vikings into this kind of monsters.

Being honest, I think the Vikings were like any other culture at this time. And I sometimes laugh with my friends that this is a little strong coming from the English, how many countries did they colonized? Like 70 countries or something around the world? [Laughs] I also find interesting that archeology today is becoming so very high tech that they're discovering more now with DNA, and they’re seeing that the Vikings had a lot of culture and poetry and a lot of mythology, and they were very complex, they had a lot of crafts. They weren’t just some killing machines, you know. Of course they were also violent, but I think that in the year 1000 every culture had their armies.

Activism has always been very important for you. You have supported environmental causes, you have worked for the Tibet, Kosovo, and the Me Too movement, among others. What problems are you currently more concerned about?

For me, the environmental issues are always the most important. I feel we need to act now, especially for the next generations, I don’t think we can hand this planet over to the people who are being born now with a clean conscience, unless we absolutely just do everything we can.

And I was hoping that in the Covid pandemic people could see how quickly the whole planet and the governments could act communally, close all the countries, discover a vaccine; it was done so quickly, it was never been done so quickly. I was hoping that people would then turn to environmental things and act like it’s an emergency, which it is. This has not happened as fast as I was hoping, and I feel we all need to do more, you know, including myself.

Do you think the pandemic has been a message from nature to humanity or something like that?

Yeah, for sure; we can get away from this, but we have to listen. I’ve been putting my hope in the fact that it’s a generational problem. The people around the world who have been ruling and all the politicians, they are in their 70s now or something. I’m hoping that when my generation is like the oldest one and we get the new generation in, that this will push out the people in power that are making decisions that are bad for the planet, but I don’t know if we have that much time though. It doesn’t look very good.

Photographs by Viðar Logi